Gene Wilder is perhaps best known for his role of eccentric candy maker and chocolatier Willy Wonka in the 1971 film “Willy Wonka and Chocolate Factory.” Born Jerome Silberman in 1933, his first major film role was in the Mel Brooks 1967 film, “The Producers,” which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. The actor also directed, produced and helped co-write many scripts, including the script for “Young Frankenstein.” Wilder’s last on-screen appearance was on the television show “Will and Grace” as Mr. Stein in 2003. By then, Wilder had mostly turned to writing, and released several books, including a memoir, titled “Kiss Me Like a Stranger: My Search for Love and Art,” which detailed his life from birth up until the death of his third wife, Gilda Radner, to ovarian cancer. Wilder passed away from complications due to Alzheimer’s disease on August 29, 2016.

“Gene was a very moral and honest person and a good example of someone that people would like to have as a friend and a mentor,” said the late actor’s wife of 25 years, Karen Boyer Wilder. “He was unique in so many ways. He was a real partner and that’s not easy to find. He helped me and took care of me from the moment we first met and encouraged me to do many things to be able to grow and explore.”

Wilder met his wife Karen in 1991 while working on the film “See No Evil, Hear No Evil.” He was studying to play a character who was deaf. As a speech pathologist, she helped train him in reading lips for the part. In a January 2018 essay for ABC News, Karen wrote, “I never pictured myself marrying a movie star. I also never saw myself spending years of my life taking care of one. But I’ve done both. Love was the reason for the first. Alzheimer’s disease, the second.”

Defining Alzheimer’s Disease

Purple is the color of Alzheimer's awareness and support.

Purple is the color of Alzheimer's awareness and support.Alzheimer’s disease is one of several forms of dementia, including vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Korsakoff syndrome and others. The disease is marked by a loss of memory and changes in personality. Each person progresses through the disease states differently.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, there are three general stages of progression: mild, moderate and severe. In the early stages of Alzheimer’s, patients may still drive, work and be a part of social activities, but feel as if they are having memory lapses—forgetting familiar words or the location of everyday objects. Difficulties may be noticed by friends and family members. In a detailed medical interview, doctors may be able to detect problems in memory or concentration.

Moderate Alzheimer’s is typically the longest stage of the disease and may last for many years. Individuals have more difficulty performing daily tasks, such as paying bills, but may still remember significant details about their life. Family members may notice frustration or anger, or the person may act in unexpected ways, such as refusing to bathe. Damaged nerve cells in the brain make expressing thoughts difficult.

In the late stage of the disease, individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, to carry on a conversation and, eventually, to control movement. As the disease worsens, significant personality changes may occur, and individuals may need help with daily activities.

In her essay for ABC News, Karen wrote, “The first signs of trouble were small. Always the kindest, most tender man (if a fly landed on him, he waited for the fly to leave), suddenly I saw Gene lashing out at our grandson ... Once, at a party with friends, when the subject of ‘Young Frankenstein’ came up, he couldn’t think of the name of the movie and had to act it out instead.”

The Wilders sought out the help of Dr. Michael Rafii, clinical director of the University of Southern California Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute and Associate Professor of Clinical Neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“I first met Gene in January of 2014 when he was 80 years old. He came into the clinic for an evaluation of his memory complaints, which his wife confirmed had been getting worse over time,” said Dr. Rafii in a recent interview. “In the process of evaluating, we take a history, perform a physical and neurological exam, take some blood tests, and review medications and try to identify if Alzheimer’s disease is the cause of that memory loss.”

“Based on the history, the exam, the memory testing and [the results of] a volumetric MRI where we measure different parts of the brain that are affected in Alzheimer’s, as well as a very specialized scan called an amyloid PET scan—with all of that information in hand, we were able to make a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia.”

Treating the Patient, Studying the Disease

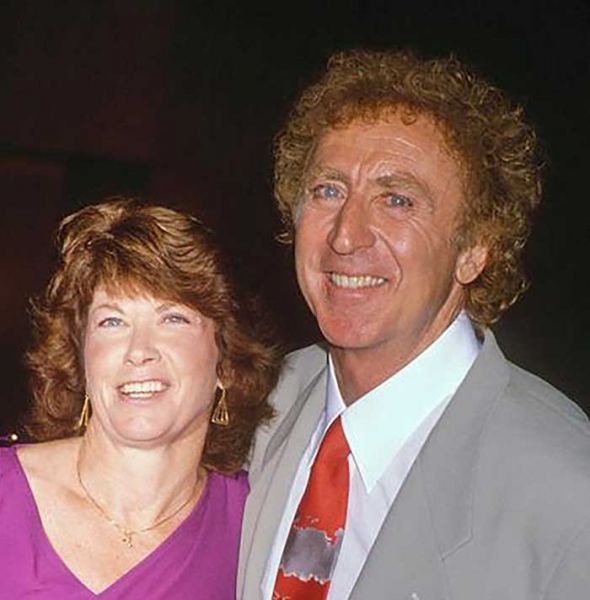

Gene Wilder and Karen Boyer Wilder in 1991.

Gene Wilder and Karen Boyer Wilder in 1991.Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. There is also no prevention or treatment to slow the progression of the disease. “There are several prescription medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help treat the symptoms of the disease. However, these medications are not effective for everyone,” said James Hendrix, director, Scientific & Global Initiatives, Alzheimer’s Association.

A recent report in the New York Times cited that simply finding patients for clinical trials is a hurdle for many companies seeking new treatments. The drug company Eli Lilly has a new treatment that may slow or stop memory loss. For the trial of the treatment, the company needs 325 patients between the ages of 65 and 85 in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. But it’s just not that easy, reports the New York Times. Only 20 percent of patients referred to the study will meet the criteria. With 5.4 million patients in the United States currently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, it is startling to think that researching the disease is so difficult.

“As researchers look for ways to prevent Alzheimer’s, there is mounting evidence to suggest that adopting lifestyle interventions combining healthy nutrition, physical activity, social and intellectual engagement may protect the brain and reduce the risk of cognitive decline,” said Hendrix. “Researchers are exploring what impact these interventions may have on Alzheimer’s.”

Recently, AARP announced a new campaign called “Disrupt Dementia” and a $60 million funding effort aimed at research for new treatments and cures. Joining AARP in this effort are UnitedHealth Group and Quest Diagnostics. “The campaign aims to help drive new diagnostics and treatments for dementias while providing education, support and hope for patients and family caregivers impacted by the physical, emotional and financial stress of dementia,” said AARP in a press release.

Staying Home

Alzheimer’s patients often benefit from a familiar environment, such as their own home, rather than institutional care, in the early and moderate stages. “I think the benefit of Gene being at home where he was familiar with everything, and knew where everything was, was extremely important for making him feel more comfortable,” Karen said. “In addition, I think it was very beneficial for Gene to have me and our housekeepers around because we were the people that really loved him the most.”

When professional help is needed, home health caregivers are there to step in and relieve the burden of care for family members. The Alzheimer’s Association offers online certification through the EssentiALZ program. The EssentiALZ exam tests understanding of evidence-based dementia care practices that are promoted in the Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Practice Recommendations.

“Studies show staff trained specifically in dementia care are able to provide better quality of life for residents and have increased confidence, productivity and job satisfaction,” said Ruth Drew, director, Information and Support Services at the Alzheimer’s Association.

Said Karen about her experience with professional caregivers for Wilder, “Based on my experience with Gene, most of the caregivers that I hired had their own unique and personal way on how to treat patients with Alzheimer’s disease. My feeling is that it’s very important to explain to them your loved one’s personal habits and needs first, prior to them starting care. Ideally, I think it should be a combined effort between the family, physician and the caregiver to ensure the best results for the patient.”

It is important, too, that the home is safe for the person with Alzheimer’s and the family as a whole. Building a comprehensive safety plan is vital as the disease progresses. The Alzheimer’s Association offers a home safety checklist for family members and professionals to walk through the home.

Caring for the Caregiver

Alzheimer’s disease has a hidden toll. Family caregivers suffer alongside their loved one as they watch the cognitive decline and behavioral changes. The toll can quickly become too much for a family member to bear if there is no help.

“At times it was very overwhelming for me. One story that comes to mind is when I was assisting him while he was writing his book. Gene wanted me to change several phrases,” said Karen. “I more or less knew what he wanted. However, he would tell me exactly what to write down. After a while, I’d read it back to him and he’d say, ‘That’s not what I said!’ It’s hard to argue with that when you don’t know what he really wants to say.”

“When Gene first started showing symptoms, what helped me the most was learning as much as possible about the disease. I did a lot of research,” Karen added. “Reading about it on the internet; I also found several helpful books and videos. In addition, I spoke to Gene’s physician, Dr. Michael Rafii, along with other experts to get a better understanding on how I could best take care of him.”

Drew said, “Too many people are shouldering the caregiving burden alone. Many people want or would welcome help, but they are reluctant or just too overwhelmed to ask.”

A recent survey by the Alzheimer’s Association of family caregivers found that 91 percent felt that caring for someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia should be a group effort among family or close friends, yet one out of three caregivers are not engaging others in the task. Some 84 percent of caregivers reported wanting more support in caring for someone with Alzheimer’s, especially from family members.

“Caregiving, especially when done alone, can take a severe emotional and physical toll on those providing it,” Drew said. “In fact, 35 percent of caregivers for people with Alzheimer’s report their health has gotten worse due to care responsibilities.”

There are support groups available through the Alzheimer’s Association for caregivers and those with Alzheimer’s. “I did go to support groups. I went to Alzheimer’s San Diego,” said Karen. “In my support group, they talked about financial planning and costs, which I think is extremely important as Alzheimer’s disease requires, in some cases, 24/7 care. This can be very costly.”

Telling the Story

Today, Karen seeks to raise awareness for Alzheimer’s disease by collaborating with the producers of “Remembering Leonard Nimoy,” Julie Nimoy and David Knight.

Karen Boyer Wilder, left, with David Knight and Julie Nimoy, producers of "Remembering Leonard Nimoy" and "Remembering Gene Wilder."

Karen Boyer Wilder, left, with David Knight and Julie Nimoy, producers of "Remembering Leonard Nimoy" and "Remembering Gene Wilder."“My dad and Gene were great friends for years,” stated co-producer, Julie Nimoy. “David and I are so honored to be producing ‘Remembering Gene Wilder: His Life, Legacy and Battle with Alzheimer’s Disease,’ which will be available in summer 2019.”

“Our goal for telling Gene’s story is to create awareness and attention for Alzheimer’s disease. So many people in this country have the disease but sadly, have never been diagnosed,” said Karen. “Our hope is that by watching Gene’s story, people will be encouraged to see their family physician if they suspect or start showing symptoms similar to Gene’s. Also, people should be hopeful for the future. They can be optimistic that a cure will be found. There’s some amazing research currently going on in this country and all over the world.”

Wilder leaves behind a legacy of laughter and love. He is remembered for his humor and charm on the silver screen. At the time of his diagnosis, he and his family chose to keep the disease quiet, wanting to let his fans remember the actor as he was, not as his disease. As the new film tells his story, the stigma of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis will hopefully fade as the actor’s vibrancy reminds viewers why they loved him. As the need for Alzheimer’s research grows, may we all remember Wilder’s pure imagination.

Follow @GeneADFilm on Twitter for the latest updates and more. Statistics for this article were found at alz.org.