Professor Peter Cramton’s recent study confirmed the HME industry’s fears—the competitive bidding system in Round 1 areas took a devastating toll on providers, caused claims to plummet and appears to have shattered the delivery system that serves Medicare beneficiaries.

Professor Peter Cramton’s recent study confirmed the HME industry’s fears—the competitive bidding system in Round 1 areas took a devastating toll on providers, caused claims to plummet and appears to have shattered the delivery system that serves Medicare beneficiaries.

Officials from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services agree that claims and providers have declined, but insist that the supply line to beneficiaries remains intact.

Cramton, a University of Maryland economist who has been watching and analyzing Medicare’s competitive bidding program, says CMS should quickly release more data to prove the point.

Cramton—along with many other auction experts—has warned that the Competitive Bidding Program is poorly designed and destined for failure.

CMS officials have doggedly defended competitive bidding, calling it a success because it has lowered costs, and done so without limiting HME access for beneficiaries.

In an interview about his latest work, Cramton responded to CMS officials who criticized his methodology as “seriously flawed” and called his conclusions “grossly inaccurate.” At issue is a key finding in Cramton’s study—a dramatic decline in claims submitted for HME products, which could be an indication that beneficiaries are losing services.

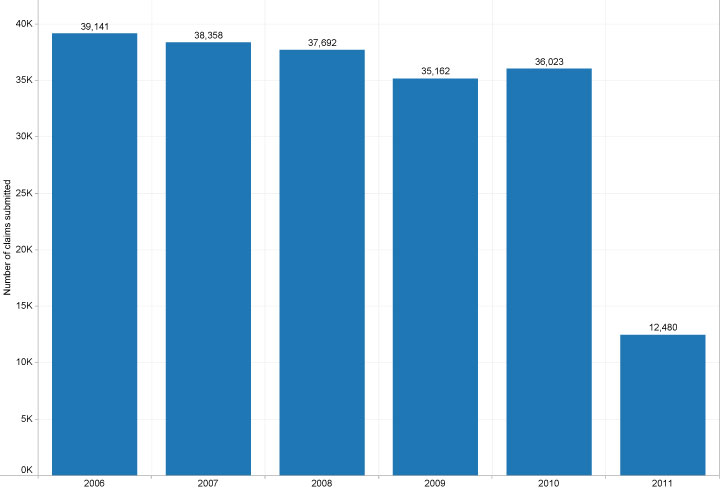

Cramton’s study, which was released January 20, involves three sets of charts created from Medicare’s own data taken from Round 1 areas of competitive bidding:

- The first set shows a sharp decline in the number of HME providers, which is not surprising since competitive bidding was expected to do that.

- The second set shows dramatic declines for claims submitted for HME products. That is surprising because competitive bidding was not expected to lower claims that severely.

- And the third set of charts shows that lack of access to HME products results in higher rates of death and hospitalization for beneficiaries with certain diagnoses such as COPD and diabetes. Again, this was not surprising data since there is no debate about the benefit of HME products.

So the second set of charts is the focus of controversy. Those charts show an average 70 percent decline in the number of claims submitted in 2011 for seven HME product categories in Round 1 areas.

Cramton used Medicare data from 2006 until 2011 for his charts. He was able to get only about nine months of claims data for 2011, so he corrected, or “annualized,” the data so it could be compared to previous years.

He also added a footnote to his study explaining that there is often a lag between the time when a Medicare beneficiary receives a product/service and the time when a claim is submitted. That could mean products have been delivered, but claim numbers have yet to rise. However, he added: “The size of the reductions in claims is so large that it seems implausible that this could be the result of lags in the receipt of claims.”

Additionally, CMS officials said that a decline in claims was expected because areas chosen for Round 1 had abnormally high DME use, a sign of fraud, waste and abuse. So, CMS said in a statement, the decline in claims is no surprise and is exaggerated in Cramton’s study.

Neither point makes any sense, Cramton said. He talked with people in the HME industry about the lag time between delivery and claim submission, and it should not make that much of a difference. “I certainly acknowledge there is some; it seems unlikely that it is that much.”

Fraud, waste and abuse also seem unlikely because of the high level of audits and oversights implemented years before competitive bidding started. At that time, there was a drop in claims, but there’s no reason to believe it would happen again to such a large extent.

It is far more likely that competitive bidding caused an upheaval in the network created among manufacturers, providers and health care institutions that delivered HME products to patients. Competitive bidding shrank a delivery network that had been in place for decades, and then stretched it.

A reasonable person would view the data and conclude that the supply system is malfunctioning, and also be concerned that beneficiaries are being cut off from HME products, Cramton said.

CMS says there is no evidence to support that, and it has been carefully monitoring to determine whether beneficiaries in Round 1 areas are experiencing rising rates of hospitalizations. “We have found nothing,’’ the agency’s statement said.

Specifically, CMS said it is monitoring: Medicare beneficiaries who were enrolled in the program when Round 1 started; beneficiaries who are actively using DME products; and beneficiaries who are likely to use competitively bid products on the basis of health conditions.

Cramton said Medicare can settle the issue by releasing more claims data. He conceded that the lag time between delivery and claim submission is an unknown factor, as is the amount of time it takes CMS to enter that information in its database.

“Of course I only see claims that are recorded in the CMS database. There is no way for me to know how big the lag is. This issue requires additional (and more recent) data to account for the lag. It would take many months to get additional data.”

In the meantime, there is powerful preliminary evidence that patient care is being compromised and the HME industry is being damaged by Round 1. This comes as Medicare prepares to expand the Competitive Bidding Program from its original nine metropolitan areas to 100 areas, or about 75 percent of the nation.

“Damage is being done now, and the longer it goes on the more difficult it is to reverse,’’ Cramton said. “The solution is to adopt a proper auction that’s been carefully designed to achieve the objective. The problem right now is the approach doesn’t lead to sustainable pricing. That needs to be fixed. Ultimately it will certainly need to be fixed, and the sooner they do it, the better.”

Competitive bidding may appear to be saving CMS money, but those savings are not real if they are offset by higher costs for hospitalization and care of beneficiaries who would have been far better off with less expensive HME products, he said.

Complaints become “inquiries” for Medicare

If Medicare beneficiaries are being denied access to HME products it would seem there would be more complaints. Well, if appears there may be, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services prefers to call them “inquiries.”

Rob Brant of the Accredited Medical Equipment Providers of America said Medicare got 54,000 “inquiries” or calls about problems in the first quarter of 2011 after the agency started Round 1 of competitive bidding in nine metropolitan areas.

“So you have 54,000 in nine areas, and now we’re going to 100 areas,” he said. “We’re going to have half a million calls?”

Georgie Blackburn, vice president for government relations at Blackburns’ Physician Pharmacy Inc., which operates in the Pittsburgh Competitive Bidding Area of Round 1, said Medicare beneficiaries are often reluctant to press complaints. These are people who are old, sick and vulnerable.

“We’re talking about the 65 and over population, and a lot of them are not cared for by spouses and children who live with them, and they just are not well enough to be their own advocates,’’ she said. “I can tell you from 35 years in this business that beneficiaries are so afraid to speak up because it’s like there’s a Big Kahuna in the sky that will take away their Medicare coverage.”